Flannery O'Connor's Vision of the Modern South

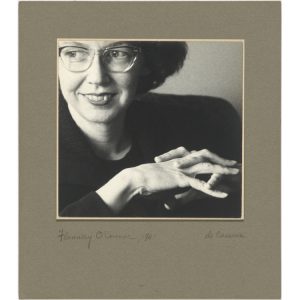

Our Core Document Collection on the role of women in American religion includes an essay by acclaimed fiction writer and speaker Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964). O’Connor has a reputation as a “gothic” novelist, but though her writing often walks the line between shadows and light, her purpose is not merely to expose the maccabre but rather to illuminate the ways in which ordinary life points towards the extraordinary and even spiritual.

O’Connor was diagnosed with lupus in 1952 and spent the last twelve years of her life largely in seclusion on her parents’ Georgia farm. Yet she still maintained a robust public speaking schedule, attempting to explain—as she does in the essay excerpted here, “The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South”—the larger redemptive purpose behind her writing.

O’Connor saw herself writing within a faith tradition long accustomed to the reality of human suffering. Her essay collection Mystery and Manners, describes her uncomfortable role as an emissary from one culture to another, and yet also reflects on the essential connection and engagement between faith and place:

The Catholic novel that fails is usually one in which this kind of engagement is absent. . . . The Catholic novel that fails is one in which there is no genuine sense of place and in which feeling is by that much diminished. Its action occurs in an abstracted setting. It could be anywhere or nowhere. This reduces its dimensions drastically and cuts down on those tensions that keep it from being facile and slick. . . . But there are reasons other than merely literary ones why the South is good ground for Catholic fiction. The writer whose themes are religious particularly needs a region where these themes find a response in the life of the people, and this condition is met in the South as nowhere else. A secular society understands the religious mind less and less. It becomes more and more difficult in America to make belief believable, which is what the novelist has to do. It takes less and less belief acted upon to make one appear a fanatic. When you create a character who believes vigorously in Christ, you have to explain his aberration. Here the Southern writer has the greatest possible advantage; he lives in the Bible Belt, where such people, though not as numerous as they used to be, are taken for granted. . . .

Writing in the post-World War II era in which ‘hope’ seemed intimately connected to scientific progress, O’Connor retained and translated a much older Christian understanding of humanity’s path towards redemption. She insisted on its relevance for the American context, frequently using her religious perspective to shine light on the deep chasms in modern American social thought.